by Ayan Shamchiyeva and Nailya Mussayeva

Introduction

While some people still believe in global conspiracies, 97% of scientists agree that climate change is real and that human activities—such as deforestation, carbon-intensive overproduction, and industrial animal farming—are driving it by producing excessive greenhouse gases (NASA, n.d.).

Climate change is no longer a matter of scientific debate, as the overwhelming real-world evidence speaks for itself. For example, world temperatures reached their highest levels ever on July 21, 2024, with a new record set the very next day, on July 22, 2024 (Copernicus, 2024). While the Global South bears the brunt of climate change, the EECCA (Eastern Europe, Caucasus, and Central Asia) region is also facing severe impacts, such as heat waves, rising sea levels, wildfires, and other environmental crises.

Although the EECCA region has historically contributed little to climate change, we now find ourselves relying on mini ventilators just to survive the increasingly unbearable summer heat. Meanwhile, the global carbon budget—the limit of CO2 emissions we can afford to emit to prevent catastrophic warming—has been nearly depleted, primarily due to the heavy emissions of industrialized nations. While climate change is often viewed as a problem of the "Western world," it’s becoming increasingly clear that we are also deeply affected.

To stress the urgency of the situation, consider the Paris Agreement of 2015, which aimed to limit global temperature rise to below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, with an aspirational target of 1.5°C (UN, 2015). However, temperatures have already risen by 1.2°C since the Industrial Revolution (IPCC, 2023), underscoring the need for immediate action. In the EECCA region, the impacts are already evident. Observed climate change in Central Asia is around twice the global average, making it one of the world's warming hotspots (Fallah&Rostami, 2024). At the same time, specifically, between 1901 and 2016, Kazakhstan's average annual temperatures rose by 5.78°C (Climate Centre, 2022). Looking ahead, projections suggest that by 2040, the Caucasus region could see a further rise of 1.3-1.7°C, leading to a cumulative increase of up to 3.0°C (CPC, 2024).

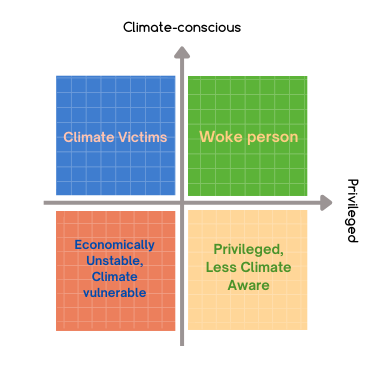

Additionally, climate change is frequently seen as an issue for the "rich" or "privileged," but the reality is that it impacts people across all social and economic levels in our countries. This brings us to the concept of climate justice, which highlights that not only do different nations and regions experience climate impacts unequally, but individuals from varying social and economic backgrounds within the same community also face these challenges and responsibilities in different ways. To illustrate these disparities, we’ve created the Climate Justice Compass—a tool that helps visualize where different groups fall on this spectrum. At the end of this article, you can take a quiz to find out your own position within this framework and discover specific actions you can take to address climate change.

Today’s situation in Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan

The environmental situation in both Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan is becoming increasingly concerning, with both nations facing a range of pressing challenges. Issues like air pollution, water shortages, land degradation, natural disasters, and waste management are putting significant pressure on both the environment and the people, all made worse by a lack of widespread environmental education.

In Kazakhstan, around 75% of the land is highly vulnerable to natural disasters, including hurricanes, landslides, floods, and earthquakes. Every year, the country experiences between 3,000 to 4,000 emergency situations, leading to injuries, loss of life, and significant financial damage. Climate change is making matters worse by increasing the frequency of floods, storms, and droughts, alongside growing shortages of essential resources like food and water (UNICEF Kazakhstan, n.d.).

Children, in particular, bear the brunt of these disasters. In 2017, more than 1,200 children in Kazakhstan died from external causes, with nearly 450 of those deaths caused by burns and fires (UNICEF Kazakhstan, n.d.).

Azerbaijan faces many of the same environmental problems. The country is at high risk for natural disasters such as flooding and water scarcity, and its ability to manage these risks is limited (ADB, 2021). Over the past three decades, Azerbaijan’s water reserves have decreased by up to 20%, with an expected additional drop of 15-20% by 2050 (ABC.az, 2023). By 2025, Azerbaijan could be one of the 13 countries with the lowest water resources per capita, with an estimated 972 cubic meters of water available per person annually (UNICEF, 2023).

Flooding also poses a significant risk, and many people are at risk of displacement due to sudden floods. The IDMC (2022) estimates that roughly 4,845 people could be displaced due to flooding. Research from 2003 to 2006 in Baku showed that a temperature rise of just 1.5°C was enough to cause a 20-34% increase in first-aid calls for blood, respiratory, and neurological issues (MENR&OHCHR, 2023).

Looking ahead, things could get worse. A 2016 study by Springmann et al. warns that by the 2050s, Azerbaijan could experience as many as 46.2 climate-related deaths per million people due to food shortages under the worst-case climate scenario.

On top of these environmental challenges, economic issues are also taking a toll. While some argue that economic development should come first, both Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan face significant economic hurdles. Income inequality is stark, personal debt is growing, and many people are spending more than they earn.

In Kazakhstan’s big cities, more than 90% of workers don’t belong to the middle class, a key factor in socio-economic stability. Almost half of these workers struggle to meet basic living expenses, and just 4.4% of the population earns enough to be considered middle class. Those with above-average incomes make up only 2% of the workforce (Jusan, 2023).

Azerbaijan faces similar challenges. About 2% of the population lives below the poverty line. According to the State Statistics Committee (2023), more than 52% of household income goes toward food, leaving little for other essential expenses or long-term investments in quality of life.

Reflecting these ongoing challenges, the 2024 Quality of Life Index ranks Azerbaijan 63nd and Kazakhstan 73rd out of 85 countries.

Understanding Our Carbon Footprint

The increasing frequency of natural disasters and environmental stressors underscores the significant role human activity plays in driving climate change. It's not just large-scale industrial emissions fueling this crisis—our daily actions contribute as well, which brings us to the concept of the carbon footprint. With 97% of scientists agreeing that climate change is largely a result of human behavior (NASA, n.d.) , understanding our carbon footprint becomes key to recognizing how each of us contributes to this global issue.

Simply put, a carbon footprint represents the total amount of greenhouse gases produced by our everyday actions. From the energy we consume to the transportation we use, these choices collectively impact the climate, making individual awareness and action critical in addressing the challenge.

It is well-known that Effective climate action requires a mix of interventions that address the multiple roles played by individuals: structural change by governments (“upstream” interventions), businesses and local authorities making sustainable options more available and attractive (“midstream”), and informational measures to shape individuals’ decision-making (“downstream”) (Hampton & Whitmarsh, 2023). Yet, the “downstream” level, which is individuals, is grouped in one big category and actions that are advised to them are very vague and not always just.

While the idea of a carbon footprint might seem distant or abstract to many people in Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan, the reality is that even small, everyday choices—like the electricity we use or the transportation we choose—add up. As explained above, climate change might seem like a far-off issue, but its impacts are becoming more and more visible and are hitting closer to home.

Impact of Colonialism and Capitalism on Climate Change

To be fair, climate measures need to acknowledge the colonial roots of the crisis. Climate change started with the exploitation of people and animals’ bodies, land, and resources during colonization, which set the stage for industrialization. While discussions often focus on the Industrial Revolution, the impact of colonization in driving this process and accelerating climate change is rarely mentioned (Wilkens and Datchoua-Tirvaudey, 2022).

The latest IPCC report from Working Group II (2023) points out that colonialism isn't just a historical cause of the climate crisis; it's also a current obstacle to effective climate action. Understanding these roots is key to creating fair climate policies. Lastly, capitalism has pushed many communities to give up sustainable cultural practices just to survive economically. This has made us forget that traditions and cultures are important and should be included and respected as essential parts of a thriving economy (CJA, n.d.).

Traditional Ecological Knowledge

The need to address climate change through local knowledge and adaptation often goes unnoticed (Ingty, 2017), yet it can be highly effective. Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) encompasses the wisdom and practices passed down through generations, showing how local communities have learned to live in harmony with their environment over centuries (Berkes, 1993). While the world has changed, making it impractical to live exactly as people did thousands of years ago, there are still many ways to integrate TEK into modern practices and continue living in unity with the natural world.

The traditional practices of the nomadic Turks offer a compelling example of the link between culture and sustainability. Ancient Turkic people, including Azerbaijanis and Kazakhs, led a nomadic pastoral lifestyle deeply intertwined with nature and sustainability. By moving their livestock seasonally, they prevented overgrazing and land degradation, which was vital for maintaining the long-term health of the land and its biodiversity.

Their nomadic way of life also minimized their ecological footprint. Instead of building permanent structures or accumulating material possessions, they lived in yurts/alachigs/kiyiz ui — temporary tents made from biodegradable, renewable materials like wood, felt, and canvas (Astana Times, 2023). These yurts were naturally insulated, reducing the need for external energy sources for heating and cooling, which further lowered their carbon footprint.

The Turkic people's deep connection with their environment helped preserve biodiversity and maintain resilient ecosystems. Their practices, rooted in ecological balance long before modern sustainability concepts, remain relevant today. Interestingly, many of these traditional practices are now being adopted in Western societies, rebranded as "eco-friendly" (UNDP, 2021).

While globalization has brought many benefits, including the exchange of innovations from around the world, it’s important not to lose sight of the knowledge and wisdom developed by our ancestors over thousands of years.

Sustainable living has long been a core value in Turkic culture, as seen in Kazakh sayings like 'If you cut down one tree, plant ten in its place' (Бір ағаш кессең, орнына он ағаш отырғыз) and 'When you see a spring, cleanse it' (Бұлақ көрсең, көзін аш). In Azerbaijani culture, similar wisdom is passed down: 'Blessings are upon those who plant trees' (Ağac əkənə rəhmət oxunar) and 'A land with water flourishes, a land without water is ruined' (Sulu el abad, susuz el viran olar). These timeless sayings remind us how vital nature is to our lives and communities.

Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Modern Times

After realizing that there is limited information and research on modern Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) in Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan, we decided to document common practices that we observe around us. Although these practices aren't officially recorded, living in these countries has allowed us to see firsthand how our people continue to follow them daily.

For example, one common practice is collecting rainwater from rooftops or streets using channels and pipes. This water is stored in barrels near homes and used for various purposes, like agriculture or even showering, as it’s believed to soften hair. Another example is the Kariz (qanat), a traditional method of channeling water through underground tunnels to fields by gravity, reducing leakage and evaporation, especially in dry regions. Also during winter, snow is collected and used to clean carpets, brightening their colors.

These sustainable practices go beyond just water management. Although specific statistics for Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan are unavailable, according to Ritchie (2020), global food waste is responsible for 6% of global greenhouse gas emissions. A major contributor is methane, which has 28 times the impact on climate change compared to CO2. Fortunately, many people in non-urban areas of these countries practice excellent food management, reducing waste significantly.

For example, leftovers from fruits and vegetables, along with stale bread, are fed to poultry and cattle, ensuring nothing goes to waste. Fruits that are nearing expiration are often turned into jams or juice (“kompot”) to preserve them. Even spoiled yogurt is strained and baked into well-puffed cakes.

In addition, the practice of reusing plastic bags until they break, and passing down clothes from one sibling to another—and eventually to cousins—shows a long-standing commitment to sustainability. This is possible by keeping clothes in good condition through sewing, repairing, and adjusting them over time.

These examples show how traditional practices, once driven by necessity, have become sustainable habits that help reduce carbon footprints and care for the environment. Unfortunately, with the rise of consumerism and capitalism, many of these eco-friendly habits have been left behind, even though they were once a natural part of daily life.

There’s also a misconception that living sustainably is a sign of poverty or limited resources, when in fact, it reflects a strong awareness and commitment to a more balanced and thoughtful way of life. Neocapitalism, with its emphasis on consumerism and economic growth, often dictates the idea that success is shown through overconsumption. While it's understandable that people want to display their achievements in this way after overcoming financial hardships, it's crucial to challenge this narrative and recognize that sustainability, rather than excess, is the path to a healthier and more equitable future.

Introduction to the Climate Justice Compass model

It's often assumed that climate-friendly actions are the same for everyone, but it's not realistic to expect people who are just getting by to cut back or spend more on sustainable, higher-quality clothes instead of cheaper, fast-fashion options. Wouldn't it be more fair and effective to direct this advice toward those with larger carbon footprints—people who consume more than they need?

That's why we developed the Climate Justice Compass model. This model considers different groups based on their socio-economic status and climate awareness, offering tailored, practical steps they can take to become more climate-conscious through a simple quiz. Recognizing that no two lives are alike, this quiz model offers a way to group individuals into four distinct lifestyles, helping people reflect on their choices and climate-related behaviors.

- People often think that those highly aware of climate issues are privileged, with the time and resources to focus on climate change issues. This is partly true, and many of these "Woke people" acknowledge their privilege and take actions in the fight against climate change by recycling, consuming less, and joining environmental campaigns.

- On the other hand (or on the upper left part of the compass), there are people who aren't financially or socially secure but are deeply aware of climate change because they’ve experienced it firsthand — losing homes, living with poor air or water, or losing jobs due to climate issues. It is hard to call them privileged, but they understand the reality of climate change better than most.

- Then there are some people who aren't aware of climate issues because they’re focused on daily survival and might see climate change as a concern for the wealthy. While they prioritize immediate needs, they shouldn’t be excluded from climate action. Eco-friendly living can be both affordable and beneficial. What steps can they take?

- Lastly, we have the Privileged, less climate aware — the main target for climate education. These individuals have the largest carbon footprints, consuming excessively and relying on private transport, often encouraged by brands promoting a high-consumption lifestyle. However, being climate-conscious is becoming the new "cool," with celebrities like Leonardo DiCaprio, Matt Damon, and BTS raising awareness. This group has the potential to adopt more sustainable habits. What steps can they take to make that shift?

This categorization highlights that "Individuals" shouldn't be viewed as a single, homogenous target group when promoting a sustainable lifestyle, as each person's life circumstances can vary greatly. By filling out the quiz, you'll discover which of four categories best describes your climate awareness profile.

You can take the quiz here.

Conclusion

Today, sustainable practices are often dismissed as "Western" ideas or seen as impractical for people in the Global South, including Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan, where financial challenges are common. Many feel they don’t have the time or money to focus on being eco-friendly when everyday life is so demanding. However, these practices have long been part of our own culture. In rural areas, people still maintain Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) as part of their daily lives—not just to help the environment, but because it’s practical and saves money. Unfortunately, these traditions are often neglected in urban areas.

It's time to bring back TEK as a key part of our cultural heritage and a practical way to live sustainably in cities too. By doing so, we reconnect with our roots and realize that these practices are not only good for the planet but also for our wallets. Simple actions like eating at plant-based cafes, supporting eco-initiatives, or buying quality second-hand clothes can help bring back these traditions.

As we say in Azerbaijan, “Dama-dama göl olar” (Drop by drop, a lake forms), and in Kazakhstan, “Тамшыдан тама берсе, дария болар” (Translation: Капля за каплей собирается, река появляется; If a drop keeps falling, it will become a river).